This project was funded by the ESRC and AHRC Partnership on Conflict, Crime and Security award. This was awarded to Imperial College London, Grantham Institute for Environment and Climate Change in partnership with IBA, Department of Social Sciences and Liberal Arts. We would like to acknowledge the generous time and support the Grantham Institute and IBA staff gave to the administration of the project.

In Pakistan today, infrastructure is a site of renewed political attention. A key reason is the planning and construction of numerous infrastructure projects under China’s Belt Road Initiative (BRI). CPEC is constantly characterized as a ‘game changer’ for Pakistan, due to high expectations for it to boost national and regional economic development. The CPEC represents a powerful vision of a ‘rising Pakistan’ and emphasizes not only the importance of mobility, speed, and hyper-connectivity through a surge in infrastructural investments, but also the fundamental promise of progress entrenched in infrastructure’s future orientation in which the narrative force of development is amplified.

As this new modality of ‘connectivity’ materializes on ground, frictions emerge across some of the spaces where infrastructural projects are sited. These frictions are infused with entrenched relations of caste, class, ethnicity, and gender, as well as aspirations and legal and political claims to citizenship, modernity and regional identity. Our research has mapped the discursive and material trajectories of these projects, as well their impacts on the material underpinnings of everyday life. Our research also looks at how these infrastructural projects/spaces represent different manifestations of uncertain urban development trajectories, from contested land uses to speculative frontiers of property making.

The people, both residing in and outside of these spaces, articulate a range of on-going concerns and future predicaments; from land dispossession, livelihood displacement, ecological degradation to anxieties over securitization and surveillance, as well as anticipations for development.

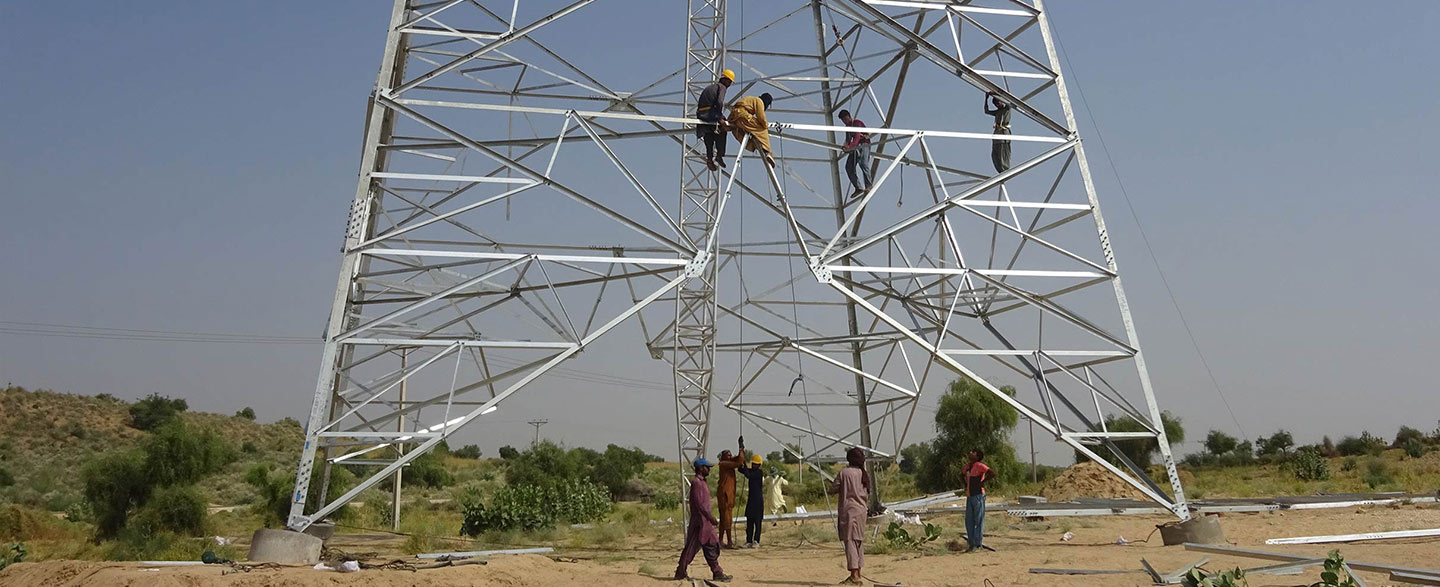

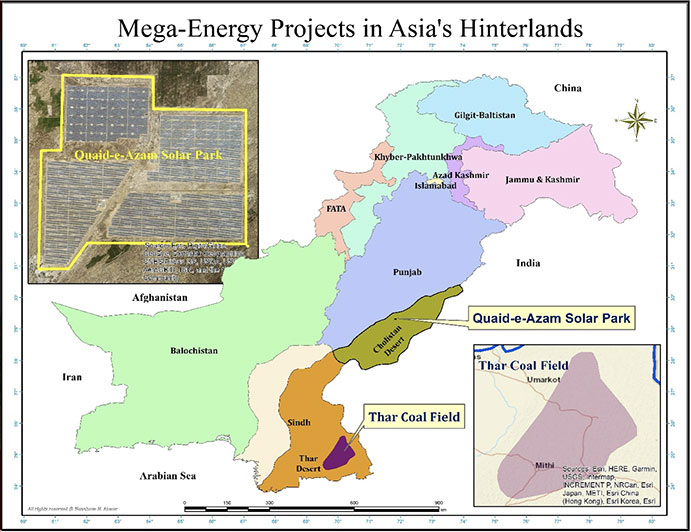

This research has focused on two mega-infrastructural projects in Pakistan

Two seemingly contrasting energy sources – high-tech photovoltaic panels and coal dependent energy – have become symbols of Pakistan’s energy crisis. Photovoltaics are associated with clean-green or renewable energy, futuristic sustainability, ultra-modernity and international political energy consensus. Coal mining and fossil fuel-based energy conjures images of unsustainability and pollution. In Pakistan both are coping strategies for a nation negotiating the crisis of a degraded grid, energy shortfalls, rising electricity consumption, and a mounting current account deficit due to reliance on imported oil. Both projects have been constructed on a ‘fast track’ basis to draw investors and are situated in remote regions: the Thar Desert, which covers the eastern Sindh province and the southeastern portion of Punjab province, and the Cholistan Desert, which adjoins the Thar desert spreading into Punjab and India.

These ecosystems are under threat of climate change with rainfall patterns shifting and long spells of hot weather and droughts impacting pastoral livelihoods. A significant number of agro-pastoral communities inhabit these regions and land holds special meaning in their social worlds.

The projects are built on public and private land that has been used for residential purposes as well as subsistence farming and livestock grazing by different communities: the Hindu scheduled castes of Meghwar, Bheel, and Kolhi as well as Muslim Chounra and Sangrasi in Thar, where pastoralists are popularly known as dhanaars; and the Muslim, Seraiki speaking Channar and Shaikh castes in Cholistan, District Bahawalpur. The Channar pastoralists are often referred to as cheru. The single most important issue that has emerged from our research interviews was people’s perceptions about the livelihood impact from the acquisition of land for these projects. Respondents regularly articulated that their life is directly/indirectly ‘linked to land’.

Our research has relied on various published government documents and consultant reports as well as in-depth interviews, informal discussions, questionnaire surveys with a stratified sample of 626 respondents according to identity markers such as gender and caste; focus groups with various stakeholders and villagers involved in or affected by the projects. We also conducted media monitoring of the projects in major newspapers (English, Urdu, Punjabi and Sindhi). Participant photography was included where villagers were encouraged to take pictures and share stories about anything they felt important in their lives along the themes of ‘fears, anxieties, future’ related to land and livestock. Interviews with communities represent Hindu and Muslim castes and ethnicities and occupations in the villages in both Thar and Cholistan and were selected based on initial discussions with key informants, such as a village head, who facilitated access to communities. The digital storytelling in Thar was facilitated by Karachi Urban Lab’s Senior Research Associate, Mr Vikram Das, who is from Tharparkar and is currently pursuing his PhD in Anthropology at Humboldt University, Berlin; and Research Associate Ms. Nirmal Riaz, who is from Sindh and is now pursuing her MPhil in Anthropology at Heidelberg University, also in Germany.We share a digital storytelling based on the participant photography of a male pastoralist MS Meghwar [pseudonym], whose hamlet of Khetji ji Dhani is in the village Gorrano, where a large reservoir has been constructed on 1500 acres of land to contain the discharged underground water flowing from the first phase of open-pit coal mining in the Block II coal-field area. The Gorrano reservoir is a contested site between the SECMC and the villagers with competing narratives: the SECMC and the Thar Foundation promoting the area as a site for ecotourism, while the villagers contend ecological destruction and land dispossession. Here, SM Meghwar’s digital storytelling captures not only the ongoing transformation from the perspective of a pastoralist, but also conveys a sense of how new routes, boundaries, walls are assigning new meanings to spaces and instigating localized understandings of economic and social uncertainty.

SM Meghwar is a dhanaar (pastoralist) who lives in the hamlet Kheji Ji Dhani, in village Gorrano, Thar, Sindh. SM owns 6 cows and 15 goats. When Vikram met him during fieldwork in November 2017, SM consented to participate in a photography project to capture visually a story about the transformations underway in his village due to the construction of the Gorrano reservoir. Hamlet Kheeji Ji Dhani is located near the boundary of the Gorrano reservoir as well as a bypass road that was under construction. As a dhanaar, SM regularly visits with his livestock and other pastoralists - especially in the bheelar season of vaskaro - the marha (valleys) and gauchers (common land). In bheelar season, people in Thar harvest crops and the agricultural and guacher fields are readied for animals to feed on grass, bushes and remains of crop. For the villagers, the bheelar season is significant because it enables the livestock to feed freely and become healthy and fat. At the time, SM was waiting for the onset of the bheelar season.

From 2nd to 8th November 2017, SM captured numerous images from a digital camera the water flowing from the Gorrano reservoir; the agriculture fields; a neighbor’s burial; animals feeding on guacher land; a bypass under construction; and the familiar routes that are disappearing. In his own words, SM narrates the significance of the images, highlighting his anxieties about an uncertain future due to the construction of the reservoir. SM’s descriptions are provided in the original dhatki with English translation.